By the time the Springboks toured New Zealand in 1981, tension had been simmering between the two nations over South Africa's apartheid regime for decades. Calls for formal and informal sporting boycotts had been made for years, and several countries and sporting bodies already refused to compete with or against South Africans until the regime was lifted.

After then Prime Minister Norman Kirk called off a planned Springbok tour of New Zealand in 1973 because of threatened civil unrest, his government suffered defeat in the 1975 general election. The new Prime Minister, Robert Muldoon, repeatedly stated that "politics should stay out of sport".

The All Blacks toured South Africa in 1976, a tour that wounded New Zealand’s reputation internationally, as hundreds of people were killed as South African authorities cracked down hard on rioters in Soweto.

As the 1981 tour approached, public opinion was evenly divided, but Muldoon stuck to his belief that sport and politics shouldn't mix, so, in July, the South Africans arrived.

The challenge is laid down

Despite the history, the Springboks were welcomed with a pōwhiri at To Poho-a-Rawiri marae. Seven of the nine Māori Councils that made up the national Māori Council were against the tour. One was undecided and Tairāwhiti was the only one that supported the tour.

Māori Council President, the late Sir Graham Latimer, made it clear at the pōwhiri that the Springboks were not being welcomed with open arms.

He said he attended the pōwhiri only to bring a message that the Springboks must help to bring about change in their country. “There can be no doubt in my mind that we will not be making another such welcome on a Māori marae – I emphasise that point – unless your government can show it is prepared to change its policies on apartheid. We hope we can look forward to a time in the not-too-distant future when you could be welcomed on any marae. It would be a pity if this could be looked upon as the last international tour by South Africa".

Listen to a recording of the pōwhiri(external link)

Three things you didn't know about the 1981 Springboks tour(external link)

New Zealanders against apartheid

Between July and September, there were three games planned against the All Blacks, one against the New Zealand Māori side, and another 12 against provincial teams.

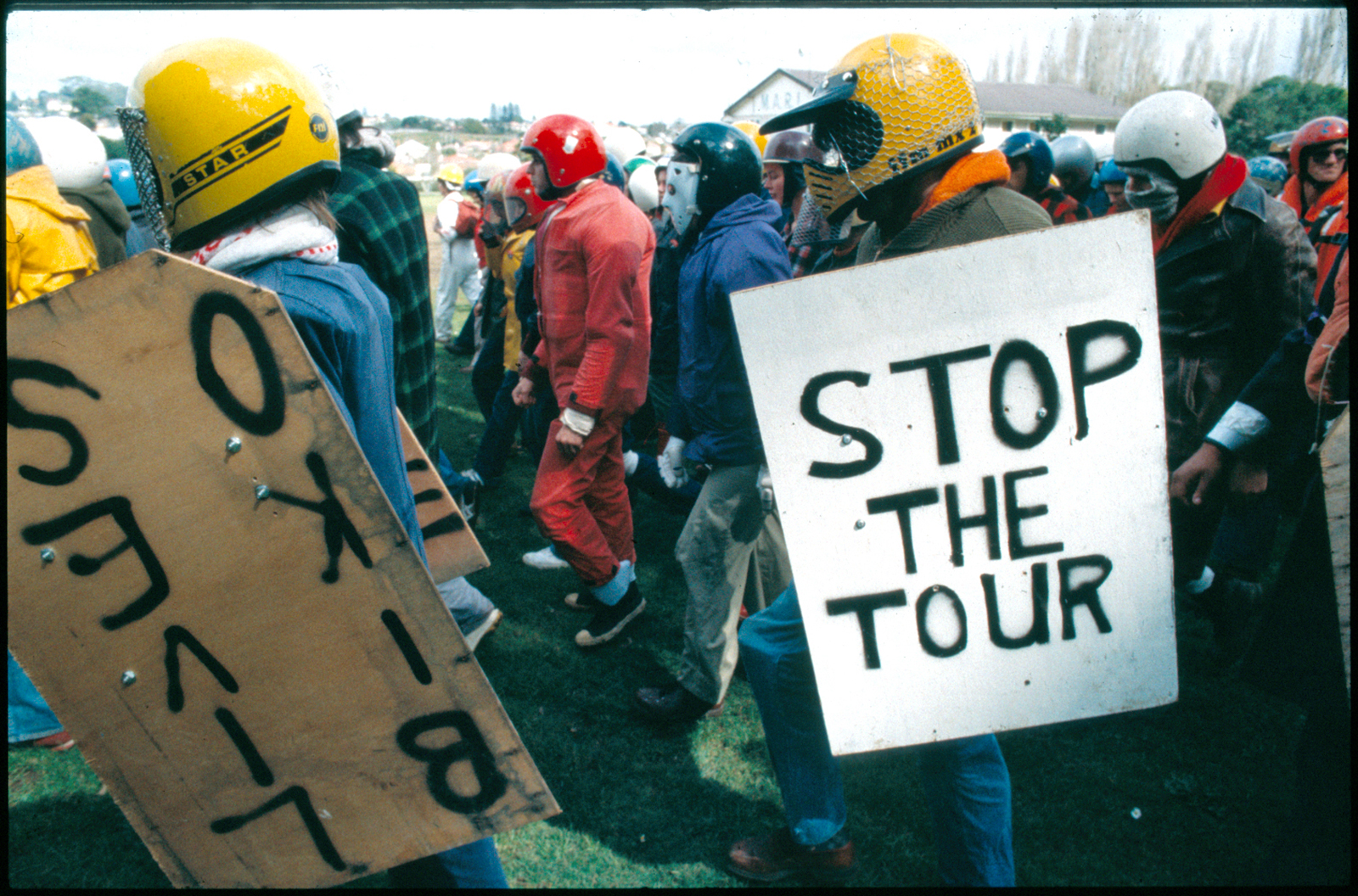

The first game, against Poverty Bay in Gisborne, set the scene for what would accompany every fixture: tour protesters, tour supporters, and the police facing off, often with violent results.

The second game, against Waikato, was called off after protesters stormed the field.

By the time the second test match was played, in Wellington, it was more like a battlefield than a rugby ground: 7000 protestors gathered, attempting to block both road and pedestrian access to Athletic Park. While the police formed barricades to allow spectators through, rugby fans lashed out at protesters.

The All Blacks won the test series, defeating the Springboks in the final test in Auckland. Fighting erupted outside Eden Park, and protestors hired a light airplane and dropped flour bombs on the field.

The Springboks went home, but the change to New Zealand was seismic – 150,000 people had protested more than 200 times across 28 locations. It was the worst civil disobedience the country had ever seen.

Even among those who weren't as invested in the outcome, there was still a sense that the tour was a watershed moment for New Zealand, and South Africa. Photographer John Selkirk covered the tour, and told Stuff that as a journalist, he was neutral, but "was acutely aware that the 1981 tour was history in the making and such an event was never going to happen in New Zealand again".

For many, the fortieth anniversary has come with a reckoning they may have been on the wrong side. Brothers Lindsay and Bryce Amner were teenagers when the tour came to Hamilton. Lindsay had a ticket to the game while Bryce was amongst the thousands of anti-tour protesters who marched on the stadium, causing the game to be cancelled.

They've made a documentary about their experiences(external link) – Lindsay now says he "was on the wrong side of history on that one… but it was not until I got home that I realised Bryce had been a part of it".

The 'BIKO LIVES' sign in this image refers to Bantu Stephen Biko, a South African anti-apartheid activist who was beaten to death while in police custody.

The end of apartheid

Negotiations to end apartheid in South Africa began in 1990 and culminated in the 1994 general election – South Africa's first with universal suffrage. Nelson Mandela, who been released from prison in 1990 after first being imprisoned on Robben Island in 1964, was elected President.

Visiting New Zealand in 1995, Mandela told leaders of the Kiwi anti-apartheid movement that when he and fellow prisoners heard the Waikato game had been cancelled by protests, "it was like the sun came out…

"You elected to brave the batons and pronounce that New Zealand could not be free when other human beings were being subjected to a legalised and cruel system of racial domination.

"In time, this nation and its government could stand tall as one of the most committed supporters of the anti-apartheid cause," Mandela said.

Today, we're facing the climate crisis, possibly the biggest challenge we have ever faced. Climate change will increasingly affect our people, our businesses, our whakapapa – past, present, and future. We can stand tall on climate action, but we need to act now, and with urgency. Our actions on climate change will be our defining moment.

Will we be on the right side of history?